Unless otherwise noted, all information was taken from the National Register Nomination, which added the Pulaski County Courthouse to the National Register of Historic Places. A significant amount of work for that application was completed by Lynda Irving, who was the Pulaski County Historian at the time. All citations for information can be viewed on this document. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/edb00616-f1fe-4008-8efc-7f0b3a. Some photos are from the same source; others are from Karen Fritz.

Unless otherwise noted, all information was taken from the National Register Nomination, which added the Pulaski County Courthouse to the National Register of Historic Places. A significant amount of work for that application was completed by Lynda Irving, who was the Pulaski County Historian at the time. All citations for information can be viewed on this document. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/edb00616-f1fe-4008-8efc-7f0b3a. Some photos are from the same source; others are from Karen Fritz.

The Two That Came Before

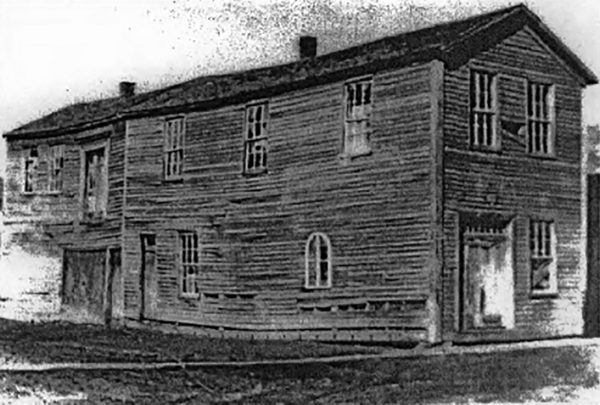

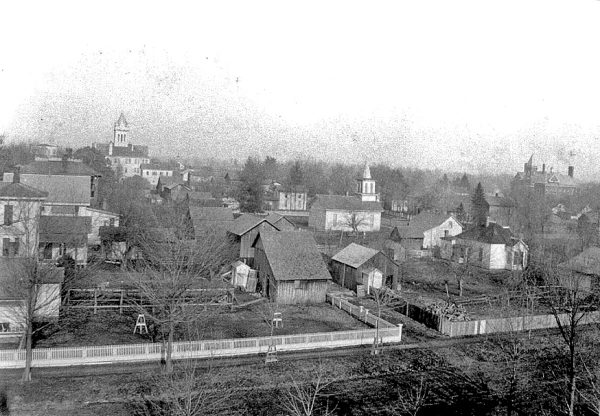

The Pulaski County Courthouse, built in 1895, is the third to be located on the courthouse square in Winamac and the fourth government center since the formation of the county in 1839. The first courthouse, a “good hewed log house” held both the first circuit court and a school. In 1843, the county commissioners began the construction of a frame courthouse on a donated lot but soon ran out of money; the building was finally completed in 1849. A second courthouse, a large two-story brick building, was completed in 1862. The county jail, a separate building, stood alongside it on the public square.

Improving The Seat Of Government

Improving The Seat Of Government

By 1890, talk again turned to improving the seat of government. The following “informal history” of the existing Pulaski County Courthouse was written by Linda Irving, the Pulaski County Historian:

Hear ye! Hear ye! Hear ye! Court is in session, the Honorable Judge George Burson presiding. Only the court isn’t in session and the judge isn’t presiding, because he can’t get into the court room. The door is locked. The date is 2 September 1895, and the judge is not happy.

Two years before Judge Burson had evaluated the old courthouse and written a report to the Commissioners condemning it. When the Pulaski County Commissioners met in January 1894, they decided to build a new courthouse. The project was not greeted with the greatest enthusiasm by anyone, except the judge.

The Commissioners Were Divided

Even the commissioners themselves were divided over the necessity of a new building. The old courthouse was only 32 years old, and while local opinion held that “it wasn’t very nice, or overly good, it was no worse than it had been for years.” It could do duty for a while longer. The argument put forth in support of the project was that the old building did not sufficiently protect county records, especially the land records. If anything happened to them, it would be a calamity of enormous proportion. It was further pointed out that interest rates were low and materials cheap. It was definitely time to build, On the other hand, taxpayers noted that the reason interest rates were low and materials cheap was that everyone was broke—including (and perhaps especially) them. Pulaski County was going through the worst financial depression it had experienced in years.

Crops had failed two years in a row and money was tight, but when it came to the protection of county records, the decisions of the Commissioners were final. They did not need public approval, and that was a good thing, because they were never going to get it.

Commissioners Play Games

Commissioners Play Games

Having decided to push ahead with a new courthouse, the Commissioners soon encountered a new problem. There were simply too many architects who submitted proposals. Twenty architects descended on the board on the morning of 5 March 1894, prepared to stay until all plans and specifications had been thoroughly gone over. That, combined with the Commissioners’ regular business, resulted in a mad house of activity.

After much discussion, all but six of the architects were dismissed. Then it seems that our three Commissioners were going to change their minds about building a new courthouse because they were immediately threatened with lawsuits. If they didn’t choose a design, they would be sued by all of the architects for the cost of preparing the plans.

The Commissioners pressed on and chose the design submitted by Rau and Kirsch of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who offered them an all-expenses paid junket to Waukesha, Wisconsin, to view a courthouse built from the same plans. That was when our Commissioners learned something it’s taken another century for Congress to get a handle on. Don’t accept gifts or gratuities of anything else that looks even vaguely like fun from people who want the taxpayers’ money.

Immediately, there was a lengthy petition filed, the chief charge of which was that “the Milwaukee firm had exercised rather an undue and unfair influence upon the board.” So the courthouse matter took a new turn, and, after deciding that the Wisconsin plans weren’t so good after all, the firm of A. W. Rush and Sons [A. William and Edwin A. Rush] of Grand Rapids, Michigan, was awarded the contract signed by Commissioners Maibauer and Hiland but not by Commissioner Welsh, who was rapidly becoming sick and tired of the whole things (and who didn’t want to build a new courthouse anyway, so there).

The Circus Continued

The circus continued, with the next act being the contractors. Seventeen bids ranging from $42,200 to $52,457 were received, and the contract went to the low bidder, Jordan E. Gibson of Logansport. Again there were objections. The architect said that the courthouse couldn’t be built for that little money. Auditor Bouslag said, “Let him try. It’s our tax money.” And the argument was on again for the rest of the day, and, after the Commissioners recessed for supper, it was continued down on the street corner. There were no blows struck, however, and Gibson did get the job.

The circus continued, with the next act being the contractors. Seventeen bids ranging from $42,200 to $52,457 were received, and the contract went to the low bidder, Jordan E. Gibson of Logansport. Again there were objections. The architect said that the courthouse couldn’t be built for that little money. Auditor Bouslag said, “Let him try. It’s our tax money.” And the argument was on again for the rest of the day, and, after the Commissioners recessed for supper, it was continued down on the street corner. There were no blows struck, however, and Gibson did get the job.

The building was to be 88 feet by 90 feet on the ground, 32 feet from the top of the basement to the roof and 106 feet from the ground to the top of the tower. It was to be built of the best Bedford, Indiana, limestone outside and brick inside. Steel lath, stone wainscoting in the halls, dead floors in the rooms, and tile floors in the halls were to make it almost fireproof.

It was to be completed by 1 September 1895. The contractor received the old brick courthouse, which had to be removed to make way for the new. The records and offices were moved to the second floor of the Vurpillat opera house, except for Recorder McKinsey. He said his game leg would never make it up all those stairs. Since the opera house was already overcrowded, no one objected to his moving to J. F. Yarnell’s office on the corner of South Market and Jefferson Streets.

Court was held in the old Holsinger hall over Hodson’s exchange at the corner of Monticello and Pearl Streets. It took only two days for the old building to come down and for work on a new building to begin. Huge slabs of stone, a foot or so think, was shipped in by rail and hauled on flat-top wagons to the public square. The heavy pieces were placed on strong trestles, where workers used hammers and chisels to cut and trim the pieces as prescribed by the drawings. Then they painted numbers on the reverse and awaited hooks from steam operated derrick that lifted them into specified places on the structure.

Even though construction was well under way, there was still grumbling in the ranks. There were complaints about workers getting the stone stained with clay—stains which could not easily be removed. There were complaints from the workers about low wages, and several went on strike and quit working. But as editor Gorell [of the Winamac Democrat] said, “$6.00 a week beat idleness by about 600 cents.” The men were easily replaced. Times were hard in Pulaski County.

Even Great Times Don’t Last Too Long

Unfortunately, even great times only last so long, and by the end of December a restraining order was filed against the commissioners for allowing a number of changes in the plans and specifications amounting to nearly $10,000 over the original contract total. They added a boiler, pumps and fittings, a well, an extra door to the boiler room, extra concrete, sewer pipes, etc., etc.

They were told to please restrain themselves from further improvements.

Which Brings Us Back…

Which brings us back to 2 September 1895 and Judge Burson. Even though the courthouse was completed—mostly—the commissioners had not yet accepted it. It was still in Contractor Gibson’s hands, so when Sheriff McKay went to open the courtroom door, he was turned away.

The court ordered the door opened via the crow bar route if necessary. After considerable talk that was mighty hot at both ends and not particularly cool in the middle, a truce was patched up. Gibson was assured he wouldn’t be held accountable for any damages and the door was opened. No crow bar was needed.

Courthouse Accepted

On 7 September 1895, the commissioners formally accepted the courthouse from the contractor for $52,179.90. Gibson promptly left town for Rochester, Indiana, where he laid [the Fulton County courthouse] cornerstone two weeks later.

An interesting sidelight to this whole affair is that the same architect who fought to keep Gibson off of the Winamac project recommended him for the Fulton County job.

The Rascals!

And the commissioners? The voters had the last word, and the word was, “Throw the rascals out!” And they did.

Next month we’ll bring you the plans to save the Courthouse.