Information from the 1990s, when we Received the Violin

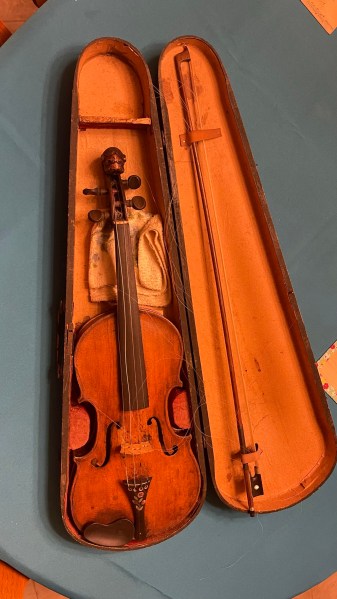

This “ole” violin was handmade in the year 1647 at Beaver, New York.

This “ole” violin was handmade in the year 1647 at Beaver, New York.

It was hand-crafted by a Bavarian named Elmer Gruber. He came from a long line of German cello and violin makers who migrated from Bavaria to Canada. The violin came to the Lindesmith family at the close of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. It now rests in the Pulaski County Museum at Winamac, Indiana.

Note: Walter Szymanski of the Winamac vicinity, who collects violins, thinks this violin may have been made by Jacob Stainer of Germany in the 1600s. Stainer was the only violin maker who used a lion’s head for a scroll, although he also made regular scrolls. (07/04/1992)

PCHS Note: Read on. This violin is not from the 1600s.

Information from the Lindesmith Family

In 1969 while under repair, a date of 1647 (date of manufacture) was found inside the violin. It was believed to be made in or near the Watertown, New York area. I will endeavor to give you factual information as it was passed on to me concerning the violin. It has been in the Lindesmith family since the battle of Gettysburg. It was here that Thomas Fife Lindesmith acquired the violin. A soldier from a New York volunteer unit traded the violin to Tom for a slab of bacon. He had not had a good meal for days. The bacon looked better to him than the violin.

In 1969 while under repair, a date of 1647 (date of manufacture) was found inside the violin. It was believed to be made in or near the Watertown, New York area. I will endeavor to give you factual information as it was passed on to me concerning the violin. It has been in the Lindesmith family since the battle of Gettysburg. It was here that Thomas Fife Lindesmith acquired the violin. A soldier from a New York volunteer unit traded the violin to Tom for a slab of bacon. He had not had a good meal for days. The bacon looked better to him than the violin.

Thomas was a self-taught violinist, having learned his trade playing for barn dances and hoe downs in Ohio and Indiana. Many lonely nights were spent around the campfires during the Civil War. Tom and the New York soldier would play while the others sang. It was during these times that the chin rest was affixed to the violin. Thomas was hard pressed to play without it. It was the only part that is not original. Of course, the strings have no doubt been replaced many times.

The New York volunteer related much history to Tom concerning the violin. It was given to him by his father just prior to his death. The New York soldier’s father received it from his father. It had been in their family since just before the French and Indian Wars. The same family had it during the Revolutionary War and right up to the Civil War. It is unfortunate that Tom did not retain the name of the New York family.

Tom protected the violin through the war and during his return to Walton, Indiana after mustering out of the service. Thomas lived most of his life in the Walton area. He migrated to Winamac in the late 1870s. Having sold 250 acres of prime Cass County farmland, he purchased a good-sized lot just south of the Earl Heater residence. He built a small residence there for himself and his wife. She was a full-blooded Nez Perce Indian. [This could not be documented.] Two sons were born to this union, Kirby and Woodrow Lindesmith. [Ancestry and FindAGrave show James Kirby and Glen Wood Lindestrom.]

Tom lived until old age claimed him in his mid-90s. His wife Sarah was 100 years old when she passed away, at which time the violin was passed on to Kirby. He played the violin fluently. At one time, a string band with Kirby as its director played for dances in and around Winamac.

At Kirby’s death, the violin was passed on to Dennis Lindesmith. Dennis did not play the violin. If he had, it no doubt would have gone through World War I. Dennis put the violin on a shelf in a bedroom closet. Luckily, it was kept in its original case, which in itself is an antique collector’s dream.

At Kirby’s death, the violin was passed on to Dennis Lindesmith. Dennis did not play the violin. If he had, it no doubt would have gone through World War I. Dennis put the violin on a shelf in a bedroom closet. Luckily, it was kept in its original case, which in itself is an antique collector’s dream.

In 1969 during a renovation of the bedroom closet, the old violin was brought to daylight. It is possible it had been in the closet for over 40 years. At this time, it was given to me, Clyde Lindesmith.

Clyde, in his youth, played the guitar and harmonica while Kirby played the violin. Many long winter evenings were spent in this repose.

Upon recovery in 1969, the violin exhibited some slight long-time storage deterioration. In fact, the top had started to separate from the frame and bottom of the instrument.

The first of January 1969, it was taken to the fine violin-cello maker at Chesterton, Indiana. His name was Eugene Knapik. He, with his father, had been violin makers in Chicago for many years. Eugene, upon seeing the violin, literally fell in love with it. He agreed to put it in first rate playable condition. In nine days he sent a card stating the instrument with the freshly haired bow was ready.

Upon retrieving the violin, Eugene Knapik (being a master player) made beautiful music flow from the violin. A violinist in the Chicago Symphony played it in 1973 during a concert. It was played by members of the South Bend Symphony who rated it “excellent.” It was retained in the Lindesmith family with no talent to play it to the present date.

[At this point, it appears the original piece, typed on legal sized paper, was photocopied with the bottom end folded over the remainder of the writing. Our story thus ends here.]

2023 Research and the Rest of the Story

Greg Ludlow of Mulberry restored the violin to “display ready.” He did not see the date “1647” inside the violin, but he did say that if it came with the original case, it could be dated to the 1860s. He also noted the lion’s head scroll as unique; he has see only one other before. He could not put a date to it.

Greg Ludlow of Mulberry restored the violin to “display ready.” He did not see the date “1647” inside the violin, but he did say that if it came with the original case, it could be dated to the 1860s. He also noted the lion’s head scroll as unique; he has see only one other before. He could not put a date to it.

The appraiser with the Violin Shop of Carmel, responding to photographs and the story, said it was possibly from the 18th century (1700s, but more likely 1800s), and was “manufactured,” not in a factory, but by a group of people who worked together to produce violins more quickly and at less cost. He said it would not be worth our while to have it valued.

The appraiser with Indianapolis Violins, also responding to photographs and the story, said the violin was definitely from the 1890s. He thinks the painting on the back might be original (not added on, as we believed). He thinks it could have been made in Saxony Germany, at best, worth a couple hundred dollars. He specifically said the violin doesn’t match the story we have for it.

Flag on Back: The flag on the back, if it was original, and if it was painted as authentic, has 13 stars. The U.S. Flag had 13 stars only until 1795.

The Case

The case bears the seal from GSB, George S. Bond Manufacturing

Brad Dorsey Chat Room

Brad Dorsey Chat Room

https://maestronet.com/forum/index.php?/topic/326273-gsb-wood-violin-cases/

I recently found out that these cases were manufactured in Charlestown, New Hampshire, not too far from where I live. Here’s an excerpt from a page on a genealogy website:

“George S. Bond, a manufacturer of Charlestown, was born in that town, March 2, 1837, son of Silas and Alice (Abbot) Bond… [in 1880] he bought out the violin case manufactory that had been established in Charlestown. There was but little work done here at first, and he employed but one man. Subsequently he had to enlarge the place, and in 1893 he had forty hands in his employment and was using a fifty horsepower engine. In that year the factory was burned. Eleven weeks later his substantial new factory was ready for business. He has now a sixty horse-power engine, and he employs from twenty-five to thirty-five hands. The factory is said to be the best equipped establishment of its kind in the world, having a capacity of twenty-four dozen violin cases per day. Mr. Bond has dealings with some of the largest firms in this country…”

Response in the Chatroom

Thanks, Brad. I’ve wondered about these cases over the years. 24 dozen cases a day would certainly explain the numbers I’ve seen. I’ve noted some variation in the latching mechanisms, from simple hook-and-eye (not a great idea unless the case never leaves the house) to more complicated hook-eye-flap-and-spring mechanisms, with their own patent number. Back in the 60s and 70s, some folks had fun fixing these cases up with better liners and exterior paint, sometimes quite colorful — flowers, paisley, and such. Wonder what old George S would have thought?

PCHS Notes

To have been labeled an authentic GSB case, this case could not have come through the Civil War. It would have been 1880 or later.

To have been labeled an authentic GSB case, this case could not have come through the Civil War. It would have been 1880 or later.

Click on the photos to see them full-sized.