This month, we will share what meager history exists – at least in this book – of the Native Americans that lived on this land. Actually, this month, numerous “notes” are included, and we have actually excised portions.

[Note from the Historical Society. This book gives the history of white settlers moving in, forming governments, schools and towns. Please understand the Historical Society does not condone the tone in which this material has been presented. The Historical Society also cringes at the way this book speaks of whites entering the area, with no thought to the angst of Native Americans who were pushed out, broken treaty after broken treaty.]

For information on the source (the book Counties of White and Pulaski, Indiana, published by A.F. Battey & Co., Chicago, in 1883), see this post.

Native Americans

Native Americans

For many centuries prior to the advent of the white man, the territory embraced in what is now Pulaski County was claimed and occupied by Native Americans, or Indians. All the region of country whose approximate corners are Detroit, the mouth of the Scioto River, the mouth of the Wabash River, and the southern point of Lake Michigan, was the property of the Twigtwee, or Miami, until they relinquished portions, first to other tribes, and later by cessions to the whites.

Within this vast scope of country they had lived for many generations…. Here they were found as early as 1672, by French traders and missionaries, and here they had undoubtedly lived for centuries before.

But during the latter part of the last century, and the early part of the present one, as the resolute white men began to enter the domain of the Indians lying northwest of the Ohio River, the soil was slowly yielded to the stronger race, and the Eastern tribes of Indians began to enter the broad territory of the Miami.

Thus it was that eventually the major part of the Miami lands was relinquished to members of other tribes, and finally by them ceded to the whites.

At the time of the appearance of the whites in Northern Indiana, from 1820 to 1840, the greater portion of the Miami lands north of the Wabash River was occupied by the Potawatomi, while the former tribe occupied the country south of the Wabash.

What is now Pulaski County was ceded by the Potawatomi to the United States on the 26th of October, 1832, by a treaty held near Rochester, between Jonathan Jennings, John W. Davis and Mark Grume, Commissioners in the service of the Government,” and Wah-she-o-nos, Wah-ban-she, Aub-bee-naub-bee, and other chiefs on the part of the Potawatomi.

The Indians did not leave for their new homes west of the Mississippi until about the year 1842, though the first detachment went in 1838 or 1839.

[Note from the Historical Society: What a polite way of saying they were forced off their lands on the Potawatomi Trail of Death. This was the forced removal by militia in 1838 of some 859 members of the Potawatomi nation from Indiana to reservation lands in what is now eastern Kansas. The march began at Twin Lakes, Indiana (Myers Lake and Cook Lake, near Plymouth, Indiana) on November 4, 1838, along the western bank of the Osage River, near present-day Osawatomie, Kansas. During the journey of approximately 660 miles over 61 days, more than 40 persons died, most of them children. It marked the single largest Indian removal in Indiana history.]

The treaty of 1832 was not confirmed by President Jackson until 1836. Very soon after the conclusion of the treaty of 1832, white trappers, hunters and squatters began to appear in what is now Pulaski County, and erelong their rude log cabins could be seen here and there on the streams.

Settlement

When the first white settlers arrived in Indian Creek Township, Potawatomi Indians were every-day sights. All along Tippecanoe River and Indian Creek were favorite locations where detachments of the tribe temporarily encamped during certain seasons of the year to hunt, trap and fish.

They visited the houses of the earliest settlers to beg, trade and, in some cases, buy…. they usually had recourse to barter, offering cranberries, huckleberries, venison and other wild meat, and various trinkets. They wanted flour, meal, and all garden vegetables….

During the winter of 1838-39, some ten or twelve families of Indians wintered on the land upon which Ira Brown settled in May, 1839. Sometime after Mr. Brown’s arrival, the Indians came one day to his house to trade for a large, valuable hunting dog owned by him. They offered two blankets, two silk handkerchiefs, and two saddles of venison; but Mr. Brown shook his head, and intimated that they must raise the price…. The trade was a failure.

[Note from the Historical Society: The Potawatomi used to own the land upon which Ira Brown settled.]

In the township the Indians had built something, the use of which is not at present generally known. They dug an excavation in the earth about three feet deep, shaping it like a butter bowl, and then packed the bottom and sides with a tight floor of stones. During the afternoon they would kindle a brush fire in the excavation, feeding it until the stones were quite hot, and finishing about bedtime. They would then remove the fire and ashes, roll themselves in their blankets, lie down on the warm stones, and enjoy a comfortable sleep despite the intense cold weather. This ingenious device enabled them to pass the severest cold nights.

Mound-Builders

Indian Creek Township is quite rich in the remains of that ancient, mysterious people, known among scientists as Mound-Builders. That this country was inhabited by a tribe or race of people prior to its occupancy by the Indians, is no longer doubted by those who have made the subject a study.

Some eminent authorities maintain that they were the remote ancestors of the Indians, while others emphatically deny this and insist that the Mound-Builders were an entirely different race of people, giving as proof, among other things, the difference in the shape and size of the skull, the principal means of distinguishing the skeletons of one race from those of another.

The latter view is the prevailing one. If the citizens of Indian Creek knew that in some half dozen places in their township are the skeletons of human beings who lived upon the earth at the time of Abraham and centuries before Christ appeared to redeem mankind, the fact might cause them some surprise. This is the case.

Across the river from Pulaski is a large, earthen mound, which, in early years, was fully twelve feet high, and is yet, notwithstanding it has been plowed over for scores of years, fully five feet above the surrounding level. No doubt this mound was constructed thousands of years ago by rude barbarians, who carried the soil there in small vessels strapped upon their backs.

The mound is a very large one for this locality, being nearly 100 feet in diameter at the base, and undoubtedly marks the last resting place of some distinguished personages who were famous among their kind.

Many years ago, a minister living temporarily at the house of Ira Brown assumed the responsibilities of a resurrectionist and made an excavation in the summit of the mound, and threw out with the spade several crumbling human skeletons. The bones were very large and strong, though the smaller ones had returned to dust and the heavier ones were on the verge of disintegration.

Two mounds of a similar character, though much smaller, were discovered some distance up the river from Pulaski, and opened many years ago, human bones and charcoal being found. At two other places below Pulaski, mounds were found, and in one case opened, the usual bones and charcoal being thrown out.

What a field for thought and speculation do these mounds and their contents afford! How strange that a race of people should have once lived here and cultivated the soil and we know nothing of it save what is gleaned from their crumbling bones and earthworks! Fact is stranger than fiction.

Additional Information from the White County Section of This Book

The mounds found in this section of the State are usually sepulchral, sacrificial or memorial. The first contain the decaying bones of the dead; the second contain ashes, charcoal and the charred bones of animals and even human beings who were immolated to secure the favor of the Being worshipped; the third were erected to commemorate some great national event.

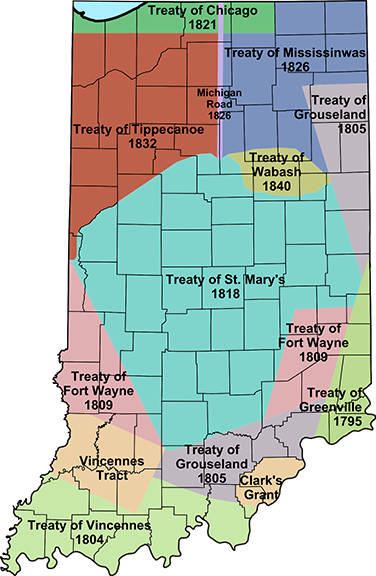

Indian Cession Treaties

[Again, a note from the Historical Society. This book gives the history of white settlers moving in, forming governments, schools and towns. Please understand the Historical Society does not condone the tone in which this material has been presented. The Historical Society also cringes at the way this book speaks of whites entering the area, with no thought to the angst of Native Americans who were pushed out, broken treaty after broken treaty. They lived here for centuries. Adding to their numbers, and beginning in the late 1600s and early 1700s, Native Americans from the east coast were pushed inland, bringing layers of tribes to the Ohio and Indiana Territories.]

[Indians] were here when the whites first came. The Potawatomi were found in possession of the soil, though the Miami claimed some rights of occupancy.

On the 2nd of October, 1818, at a treaty concluded at St, Mary’s with the Potawatomi, the following tract of country was ceded to the Government: Beginning at the mouth of the Tippecanoe River and running up the same to a point twenty-five miles in a direct line from the Wabash River, thence on a line as nearly parallel to the general course of the Wabash River as practicable to a point on the Vermillion River twenty-five miles from the Wabash River, thence down the Vermillion River to its mouth, and thence up the Wabash River to the place of beginning.

On the 16th of October, 1826, they also ceded the following tract of land. Beginning on the Tippecanoe River where the northern boundary of the tract ceded by the Potawatomi to the United States at the treaty of St. Mary’s in the year 1818 intersects the same, thence in a direct line to a point on Eel River, half way between the mouth of said river and Parrish’s Village, thence up Eel River to Seek’s Village (now in Whitley County) near the head thereof, thence in a direct line to the mouth of a creek emptying into the St. Joseph’s of the Miami (Maumee) near Metea’s Village, thence up the St. Joseph’s to the boundary line between the Ohio and Indiana, thence south to the Miami (Maumee), thence up the same to the reservation at Ft. Wayne, thence with the lines of the said reservation to the boundary established by the treaty with the Miami in 1818, thence with the said line to the Wabash River, thence with the same river to the mouth of the Tippecanoe River, and thence with the Tippecanoe River to the place of beginning.

Indian Alarms

[Note from the Historical Society. The United States did not honor any of the treaties written with Native Americans, and the government did not discourage squatters as they came in to claim land that had been in native hands for centuries. The squatters couldn’t wait for native populations to be “re-homed” west of the Mississippi.]

Immediately after the first sale of the lands of what afterward became White County, and even before, the settlers began to flock in and select new homes.

In 1832, the year of the Black Hawk war, probably twenty families were living in the county. From time to time reports came in from the west of the Indian massacres but a comparatively short distance away, and a general feeling of alarm settled down upon the pioneers on the outskirts of the thickly settled sections.

…. About the 1st of June the alarm became so intense and universal that many of the families living in White County packed their household goods in wagons and fled to the older settlements on the south side of the Wabash, driving their livestock with them.

Some persons set fire to the grass on the Grand Prairie, and the lurid glare of the flames reflected on the sky filled the breasts of the settlers for many miles around with fearful forebodings….

Companies of militia were formed in the older localities to protect the families that assembled. Notwithstanding the reports there were a number of families in White County which had the hardihood to remain on their farms, though in most cases care was taken to prevent being surprised….

They were aware that but little danger was to be apprehended, as the scene of the Indian outbreak was too far away to affect the inhabitants of White County. The majority, however, were greatly scared, and fled as stated.

A small company of about twenty men was formed at Delphi under the command of Captain Andrew Wood. The men, well-armed and provisioned, passed out on the Grand Prairie and then up the Tippecanoe River through White County going as far up as the house of Melchi Gray.

Near the mouth of the Monon, keeping a careful lookout for signs of Indians, many houses were found deserted, everything indicating a hurried departure of the owners. Others were strongly barricaded, while the occupants within were prepared to repel assaults from a savage foe. A few families went about their daily tasks as usual.

The company saw nothing whatever of hostile Indians, and soon returned to Delphi. In a little while the feeling of alarm disappeared and the families returned to their houses.

Mrs. Peter Price, then living on the old homestead a short distance west of what afterward became Monticello, relates that her family were unconscious of any circulating reports of danger from the Indians until early one morning in June, 1832, before the members of the family had arisen, when they were aroused from their slumbers by a loud shout from George A. Spencer who had ridden rapidly up on a horse and had stopped before the door of their log cabin.

The first intelligible words that fell upon the ears of the startled family were “Halloo, Peter, get up! The d*d Injuns are coming, and are killing everybody!”

It took that family about one minute to get into their clothes, and surround the messenger with anxious questions. It was decided to leave immediately, and hurried preparations were made to take the most valuable articles, and leave the remainder….

Mrs. Price and her children were taken to the house of some friend below Delphi, while Mr. Price returned to near the mouth of Spring Creek, Prairie Township, where some twelve or fifteen families had collected and had made rather formidable preparations to receive the enemy.

It is stated that a watch was kept, and every gun was loaded and in its place. It is also stated that a sort of block-house was erected, but this is probably a mistake. A few days dispelled the illusion, and the families returned to their homes. Some thought the danger was to come from the Potawatomi, while others better informed feared the Sacs and Foxes from the Mississippi River.

As a matter of fact the Potawatomi were about as much frightened as the whites, and all went to the Indian agent for advice and protection. They thought the whites were going to attack them for some reason they could not fully surmise….

[Note from the Historical Society. Regarding Native Americans, this book is useful only in understanding the lack of empathy on the part of white America to the encroachment on native lands. We add additional information.]

From the Connor Prairie Website:

The Potawatomis originated in the Michigan Territory to the north. Against the protests of the Miamis, the Potawatomis moved down the Wabash River in 1795 to the area of Pine Creek. Here they sided actively with the French against the British and later with the British against the Americans, until peace was attained in 1815.

Their settlements included Chechawkose’s Village, Mesquawbuck’s Village, Aubbeenaubbee’s Village, and other towns scattered throughout present-day Kosciusko, Pulaski, and Fulton counties. With the appearance of more white settlers in the early 1800s, the Potawatomis gradually ceded their lands, the most of which occurred between 1836 and 1841, and moved west of the Mississippi to join the other migrating tribes.

Again, a polite way of mentioning the Trail of Tears (1836) and the Trail of Death (1838).

…As a result of increased white settlement in central and northern Indiana and the pressure by the United States, Indiana was virtually cleared of its Indian population by 1840, only a generation after being opened to the settlement by white Easterners. The only visible remnant of the Indian presence were survivors of the original Indian families. In time, however, titles to their lands were also extinguished in the face of continued expansion of frontier settlement.