By Susan Joyce Dansenburg Campbell

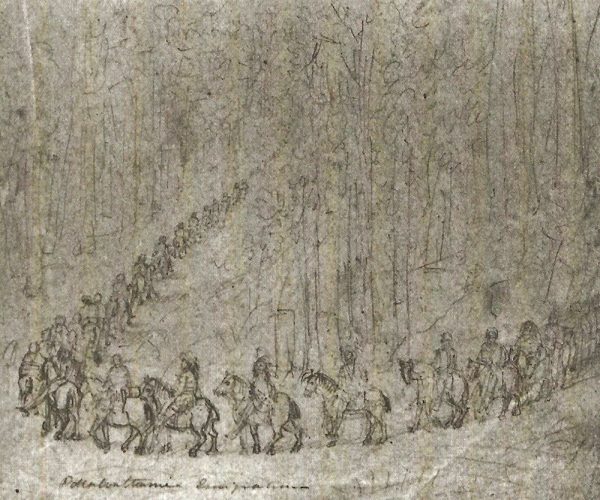

An introductory message contained in the book, Potawatomi Trail of Death – 1838 Removal from Indiana to Kansas, written and edited by Shirley Willard and Susan Campbell, Fulton County Historical Society, 2003.

Copies of this book are still available from the Fulton County Historical Society.

The story of the Potawatomi Removal from the Twin Lakes area south of Plymouth, Marshall County, Indiana to a small mission south of Osawatomie, Linn County, Kansas is a story well-documented in history. It can be found on microfilm records in the National Archives and documented in books and articles dealing with the history of the Potawatomi people. It can be found in history books, although merely annotated in some, that tell the story of places and people in the not-so-distant past, places whose names often bear remnants of the original Potawatomi name, people whose beliefs and actions formed the standards by which so many of us live today.

The Removal story is a story of people, people who lived on the land, planted and harvested their lands, built homes, lived, laughed, loved, gave birth and died. People who honored their Creator in ceremony and song, Christian and non-Christian alike. It is also a story of greed, of corruption and of fear, a story of expansion, of “manifest destiny” if you will.

But most of all it is a story of people. It is a story of families. And it is a story of my family. That is the story I want to share in this introduction.

Menominee, ogama (head man) of the village at Twin Lakes, Indiana, was a Catholic convert as were many of those residing in the village. The people of his village tilled the soil to feel their families, hunted in the nearby forests, built homes, and went to church. Menominee had invited the Black Robes, as the priests were often called, to come to his village and construct a mission church and that was done in 1834/35 according to the records of Rev. Louis Deseille (and contrary to the inscription on the stone tablet which marks the location on the lake shore, based on recollection). In 1835, the number of Indians estimated to live at Menominee’s village was 1500 living in a collection of approximately 100 wigwams, cabins and tepees. Menominee led his people in abstaining from alcohol and led them in worship and prayer twice daily. By the time Rev. Deseille visited Menominee’s village at the end of May 1835 the mission building was complete and the people of the village had made a gift of the mission building and 640 acres of land to the Church. On a list dated November 26, 1844 my fourth Great Grandfather Chesaugan’s name (also spelled She-Shaw-gin, Cheshawgan, Shehegon, Teshawgun, Shissahecon – when pronounced using a Potawatomi orthography these names all have a similar pronunciation) can be found stating that he received an annuity of $130.50 paid at Pottawatomie Mills (located on Lake Manitou, Rochester, Indiana), his portion of the annuities due the Potawatomi in the area for the year 1833. He is known to have traveled, to have been in Chicago, in Ohio, possibly as far north as Green Bay, Wisconsin. His name can first be found on the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, Ohio (though signed on his behalf by his brother). Then it is found on the September 30, 1809, treaty signed at Fort Wayne, Indiana; on a treaty signed in Chicago, Illinois, on August 29, 1821; and on a treaty signed “at the Missionary Establishment upon the St. Joseph, of Lake Michigan, in the Territory of Michigan” (wording taken from treaty) on September 20, 1828. Finally, his name is found on two treaties signed on the banks of the Tippecanoe River north of Rochester, Indiana, one on October 27, 1832, and a second dated March 29, 1836.

Records do not indicate that Chesaugan and his wife, Abita-nimi-nokoy, were Christian converts. It was customary when conversion took place that the church “assigned” a Christian baptismal name to the new convert (lists of names were kept for this purpose, the priest going down the list to the end and starting over at the top when the list ended). This was done to further separate a person from his or her tribal identity, a part of an assimilation process carried on into the present generation (information from survivors of the Catholic boarding school experience). In Chesaugan’s and Abita-nimi-nokoy’s case this was never done as far as I can determine. Certainly several of their children were converted, including their daughter, and my third-great grandmother, Sha-Note (given the baptismal name of Charlotte, she had married into a prominent Wisconsin trading family and lived with her husband Louis Vieux and children at Skunk Grove, now known as Franksville, Wisconsin until they were removed in 1836) and a son Basil (whose Potawatomi name was possibly Wassato).

And then came the Removal of 1838, referred to as the “Trail of Death.” I will not deal with all the historical facts and dates behind that; they are already presented within the text and need not be repeated here.

In 1838 Chesaugan and his family lived outside Chief Menominee’s village at Twin Lakes. He owned, in the Potawatomi way, eight acres of land (which in the currency of the day were valued at $40) planted in corn. He resided in a home much like other Potawatomi homes in the area, where he and his wife were raising their children. Their daughter, Sha-Note, my third great-grandmother, had married into a prominent Wisconsin trading family, the Vieus (in Kansas spelled “Vieux”); Sha-Note and her family had been on a removal from there to Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1836.

Chesaugan and his family did not join the Removal peaceably. According to the journal kept by Jesse C. Douglas, Chesaugan and his family “came into camp” outside Logansport, Indiana, on September 7, the fourth day of the Removal. In other words, as the volunteer militia went throughout the countryside rounding up the Potawatomi, they came upon Chesaugan and his family and rounded them up as well. The muster roll dated September 14, 1838, titled “Muster Roll of a remnant of Pottawatomie Indians of Indiana collected by John Tipton at Twin Lakes…” lists Chesaugan with one other adult make and two females (unnamed but possibly his son, Me-anco, whose name also appears on the muster roll) in his family group. Within a month following the removal a settler was heard to say, “The woods are lonely now.”

Of my family’s experiences on the Removal I have no stories. They were not passed down. By the twentieth century, through the experiences of boarding school and church, many Indian people were taught to be ashamed of their very being and fearful of their neighbors and so, out of a parent’s love for a child and the desire that the child not know fear or shame, the stories weren’t told. I do know that Chesaugan arrived in Kansas. On June 10 and again on June 17, 1843, his name can be found on letters, written from Potawatomi Creek, which request recompense from the Wabash Band Potawatomi as will as a request for Dr. P. Lykin to remain as their physician. A trading post record from October 28, 1846 shows a purchase of tobacco while an entry for January 15 shows the purchase of two shirts, sugar and a handkerchief (my thanks to Tom Ford for locating this information and sharing it with me). Archival records stored on microfilm (reel not catalogued) tell us that he appeared on the May 26, 1848, Fort Leavenworth annuity roll with his son-in-law Louis Vieux and seven of Louis and Sha-Note’s children. According to the recollections of Sophia Vieux Johnson (a daughter of Louis and Sha-Note) Recollections, her grandfather lived in a bark wigwam six miles from the family home outside Indianola, Kansas. This grandfather could only have been Chesaugan. Following that statement, there is no further word.

The militia who gathered the Potawatomi people together wanted to ensure that they didn’t return to Indiana and so many of their homes were burned behind them; their lands were eventually sold. In an address delivered before the Indiana House of Representatives on February 3, 1905, Representative Daniel McDonald stated that “the tepees, wigwams and cabins were torn down and destroyed and Menominee’s village had the appearance of having been swept by a hurricane.” They were compensated for their lands but what can compensate a person for a life?

I have no records of my family’s return to Indiana. Sha-Note died in Kansas in 1857, leaving behind several small children. Louis Vieux moved to farmland outside Louisville, Kansas, where he operated a toll bridge crossing the Vermillion River on the Oregon Trail. He married again twice and died on May 3, 1872; he is buried beside Sha-Note in the family cemetery on the farm east of Louisville, on a hillside overlooking the Oregon Trail. The cemetery is now a marked historical site.

Some of Louis’ and Sha-Note’s children took advantage of the allotments offered in Oklahoma and moved south after Louis’ death; my family returned to Kansas, where I was born. Although the custom of giving Potawatomi names continues in my family, the stories and the culture were largely put away, from what I can tell, until the 1970s. I was fortunate to discover clues left behind by my Grandmother Gracia Wade Dansenburg, great-great-granddaughter of Louis and Sha-Note, who passed over in 1970, and to have the help of family members in unwrapping these clues. Grandmother was sent to boarding school, attending Chilocco Indian School south of Arkansas City, Kansas, where it stands today. She understood the prejudices of her time but also understood the value of knowing your heritage She saw to it that as a child I was enrolled as a member of the Citizen Band Potawatomi (since 1996 the Citizen Potawatomi Nation), and it is because of her that I became interested in my Potawatomi heritage and started asking questions and looking for the clues she left.

What is the inheritance of the Removal? People who, in many cases, no longer know their language, their spirituality, their traditions, their arts. Who had these taken away from them, often by force, always by intimidation. There are those who joined together and kept these things intact and I honor them. I have met some of these Tradition carriers and have the highest respect for them. I give them my deepest thanks for sharing with me what they have. I have met those who have lost their identity, who have chosen, or had the choice made for them, to not remember who they are. It is my belief that they have lost much and I am sad for them.

As for me, I have been active in the recovery of our language, for it is my belief that within our language is our identity and without this we are no longer Potawatomi. I am active in the recovery of our arts, the beading and quill work our Ancestors did in the Great Lakes. And I am active in the preservation of my family’s history, through genealogy and the study of the history of the Potawatomi people.

In closing, I encourage you to discover you family’s stories and to share them with your children, to celebrate who you are, to celebrate the person who walks beside you, and to celebrate the person who lives next door.