Article Submitted by Brian Capouch

In early 2005, a few months after I bought the old hotel in Medaryville, I made my first visit to the White County Historical Museum in Monticello, looking for an old plat book that might give me some clues about the history of my home northeast of Monon. As I was explaining where I lived to the docent, I noticed a gentleman seated in the room who seemed to be taking an interest in our conversation. Soon, he came over and introduced himself as Ron Fry, from Winamac. He went on to tell me that my house was just a few yards downstream of the site of Cooper’s Mill, one of the earliest mills in White County. A few years before, he had done research there, and accumulated pictures and other information. He offered to send me copies of his work.

A few days later, when the promised materials arrived, I was astounded to discover that not only had there been a mill just up the road, but around the turn of the century it had spawned a village, with a dozen or so houses and a general store. The community even had a name, Milltown. The mill was originally built in 1846 by Amos Cooper, and served as one of the early beacons of civilization in the area. Its customers came from Jasper and Pulaski as well as White County. Cooper moved on, and the mill was taken over by Nelson Loughry and his sons. In 1872 they left to operate Monticello Mills, a huge mill right downtown on the river in Monticello. It stood until the middle of the 20th century, when it was destroyed by a spectacular fire which is still remembered by some.

A few days later, when the promised materials arrived, I was astounded to discover that not only had there been a mill just up the road, but around the turn of the century it had spawned a village, with a dozen or so houses and a general store. The community even had a name, Milltown. The mill was originally built in 1846 by Amos Cooper, and served as one of the early beacons of civilization in the area. Its customers came from Jasper and Pulaski as well as White County. Cooper moved on, and the mill was taken over by Nelson Loughry and his sons. In 1872 they left to operate Monticello Mills, a huge mill right downtown on the river in Monticello. It stood until the middle of the 20th century, when it was destroyed by a spectacular fire which is still remembered by some.

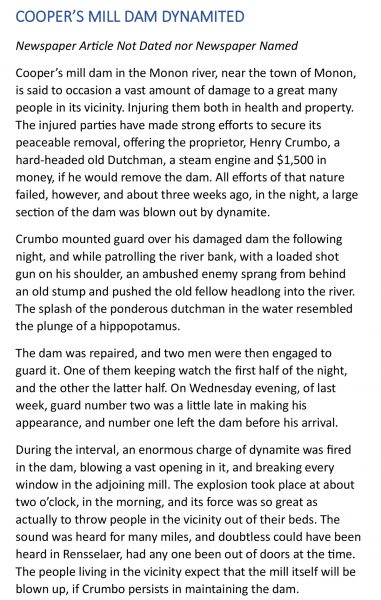

The Loughrys were succeeded by Lewis Davisson, who in 1850 with his brother Moses had constructed a mill along the Pinkamink Creek in Jasper County, and laid out the town of Davissonville there. After a few years Davisson sold the mill to Henry Crumbo, a German immigrant who had previously owned a large cattle operation in Salem Township south of Francesville.

(The dynamiting story was learned after this was written, as was the Lake Bruce mill story)

Crumbo remained until his death, but the mill business ended when he was forced to dynamite the mill dam after neighbors upstream commenced a lawsuit, contending damage to their crops because of water backing up into their fields. There was a brisk trade at the mill at the time of the dam’s destruction, and a local farmer, Uriah Hussey, soon constructed a large steam mill about a mile east of the original mill site. It operated into the 1920s. The brick building stood until just a few years ago, when it was destroyed by a microburst windstorm. Henry Crumbo’s grandson, Woodrow Wilson “Woody” Crumbo (1912-1989), was a scholarly, ground-breaking Native American artist.

Crumbo remained until his death, but the mill business ended when he was forced to dynamite the mill dam after neighbors upstream commenced a lawsuit, contending damage to their crops because of water backing up into their fields. There was a brisk trade at the mill at the time of the dam’s destruction, and a local farmer, Uriah Hussey, soon constructed a large steam mill about a mile east of the original mill site. It operated into the 1920s. The brick building stood until just a few years ago, when it was destroyed by a microburst windstorm. Henry Crumbo’s grandson, Woodrow Wilson “Woody” Crumbo (1912-1989), was a scholarly, ground-breaking Native American artist.

Because farmers in olden days grew almost all of their own food, one of the first settlement activities was the erection of mills, powered by the force of flowing water. The rule of thumb was that a sawmill would be built first, and then the product of the sawyer’s craft was used to erect a grist mill for the purpose of grinding grain into flour. The miller took a portion of all the flour that was produced, which was called the miller’s toll.

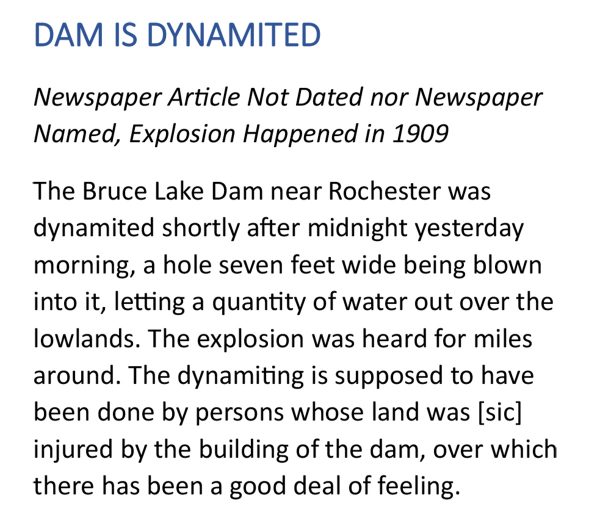

The 1883 history of Pulaski County relates that many difficulties were encountered by those who strove to set up the first mill in Winamac. The project was begun in the spring of 1839, but John Pearson, one of the proprietors, was chosen as the first Clerk, Recorder, and Auditor when Pulaski County was formed, and his “interest in the milling enterprise was overlooked.” Work proceeded slowly until 1841, when brothers Stephen and Abraham Bruce bought into the operation, and in late 1841 the mill began sawing wood. A few months later a set of grinding buhrs was installed in the same building, “and by means of suitable shafting was set in motion by the same water which propelled the saw.” This combined mill served the community until 1875, when a new 3-story grist mill was constructed. It was powered by water until 1882, when, similar to the situation which befell Cooper’s Mill, a lawsuit filed by upstream farmers forced the destruction of the dam. A 20-horsepower steam engine was then installed, and the mill continued operation in this manner for many years thereafter. In the mid-1870s another grist mill was constructed near the train depot by J.C. and H.D. Wood, driven by a forty-horsepower steam engine, with a capacity of 45 bushels of wheat per day.

Downstream in Indian Creek Township, the village of Pulaski directly owes its existence to a pair of mills (a sawmill and a gristmill) which were constructed in 1854. These mills were substantially larger than their counterparts in Winamac of that time, and the patronage generated there led David Short, brother of one of the mills’ operators, to establish a town alongside. Pulaski was platted in the fall of 1855, with 36 lots laid out. Sixteen more lots were added shortly thereafter. The sawmill ceased operation about the time of the Civil War. At roughly the same time, the grist mill was purchased by Hugh Lowe, a large landowner in Monon Township, White County. Lowe had engaged in milling, first at a sawmill and subsequently a grist mill, at the mouth of the Little Monon Creek near the village of West Bedford, beginning about 1840. Lowe’s Mill was just a few miles downstream from Cooper’s Mill.

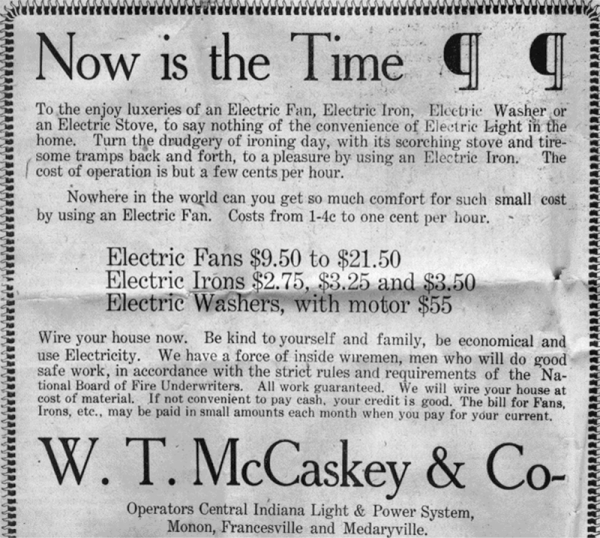

The Pulaski mill was an important business in town until about 1912, when the W. T. McKaskey Company bought it, with the stated intention of converting it into a power plant. To the disappointment of the community, nothing further ever happened. The mill stood abandoned until it burned in 1920.

Up in Medaryville, the marshy headwaters of the Big Monon Creek lack vigorous flow, and the first mill was a steam-driven apparatus which commenced operation in the spring of 1877. It was located on the south side of town near the railroad. Shortly after it began operation, it burned. It was quickly rebuilt on the north side of town in the J. C. Faris Addition, “250 yards east of the tracks and about the same distance north of Pearl Street.” With the advent of E. W. Horner’s multitude of business interests in town, he and his partner Ed Elston purchased the mill, and operated it until Horner turned his attention fully to his bank and large mercantile business about 1895. It was purchased by John Burlew, who ran it until it was destroyed by fire in 1910. The buhr stones were saved undamaged, and are on display at the small memorial mall next to the fire station.